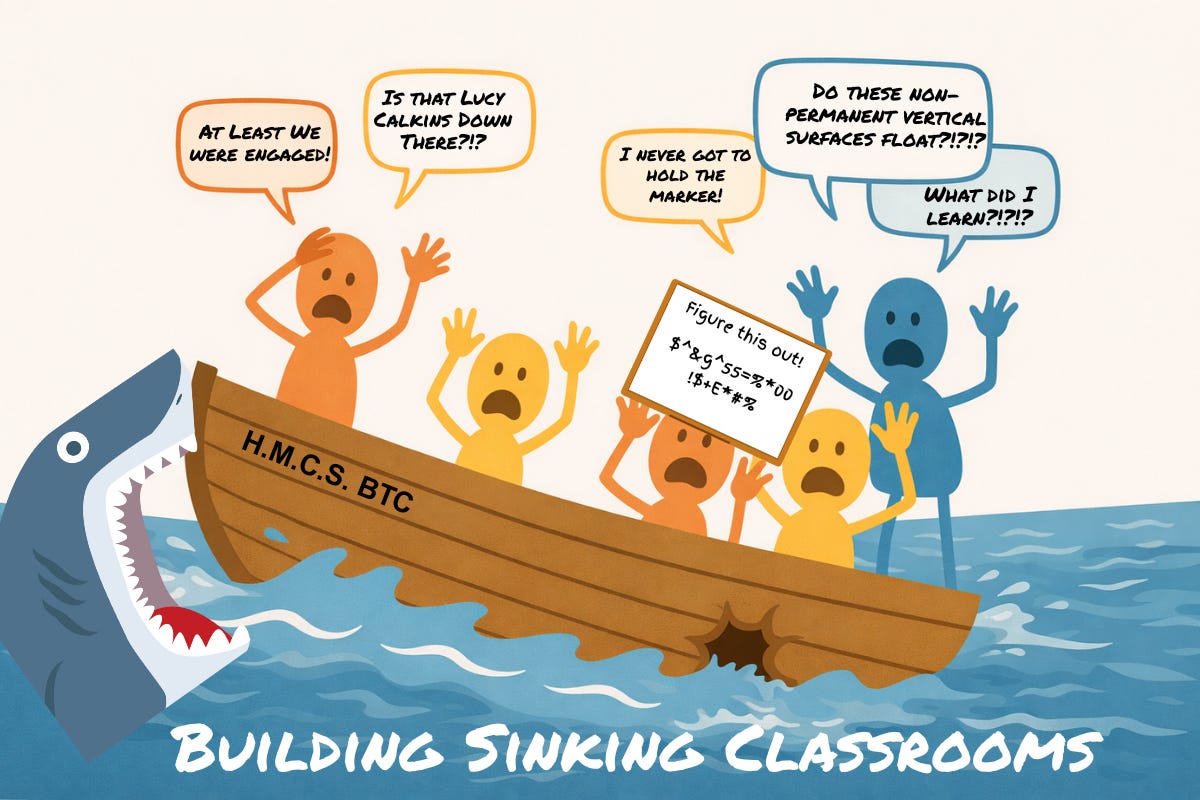

Building Sinking Classrooms

May I have some evidence please?

The Challenge of Student Thinking in Mathematics

As teachers, we are constantly searching for that elusive spark that ignites genuine student engagement, fosters deep understanding, and truly makes our students think, especially in a subject as foundational as mathematics. We know the struggle: it can feel like a daily battle against disengagement, where students go through the motions without ever building real understanding.

Enter Peter Liljedahl's "Building Thinking Classrooms" (BTC) framework. It has rapidly gained significant traction, promising to revolutionize our classrooms into dynamic spaces where students are actively thinking, collaborating, and deeply learning. According to Liljedahl, his work is rooted in over 15 years of observations in K-12 math classrooms, where he identified a pervasive and alarming issue: students were simply "not thinking." His observations suggested that a large proportion of student time was spent in what he categorized as non-thinking behaviors. Across overlapping categories of observed activity, he reported that much of students’ time involved mimicking procedures, stalling, or faking understanding, while only about 20% of students engaged in what he identified as genuine independent thinking. He attributes these "non-thinking behaviors" to deeply ingrained "institutional norms" that inadvertently stifle authentic thinking.

The Promise of Building Thinking Classrooms

The central tenet of BTC is compelling: "thinking is the precursor to learning". To combat the observed lack of student thought, Liljedahl developed 14 "optimal practices" designed to cultivate a classroom environment where deep mathematical learning can thrive. These practices are comprehensive, addressing everything from how we select tasks and group students to classroom setup and teacher questioning strategies. For instance, BTC advocates for initiating lessons with "thinking tasks," forming "visibly random groups" to foster collaboration, and having students work on "vertical non-permanent surfaces" like whiteboards, to encourage risk-taking. The teacher's role fundamentally shifts from direct instruction to that of a facilitator, guiding students with "keep thinking questions" rather than providing immediate answers.

On the surface, all of this sounds incredibly promising. Proponents of BTC confidently assert that these practices are supported by research showing they optimise the conditions for students to think, thereby increasing engagement and learning. They point to a “powerful impact on learning” and claim that students’ mindsets shift rapidly, with many beginning to think and contribute more actively within a matter of weeks. Early findings reportedly suggested that these approaches were effective in engaging students in mathematics and in reducing non-thinking behaviours.

It is easy to understand why BTC resonates with teachers and administrators who are eager for classrooms that feel more collaborative, energetic, and student-centered. It is precisely because this vision is so appealing that the question of evidence matters so much.

But Let’s Be Clear: What Does “Research-Based” Actually Mean?

While enthusiasm for BTC is undeniable, and the vision of fostering student thinking is profoundly appealing, a closer examination of its research foundation reveals a far less certain picture. In education, to describe an approach as “research-based” is to invoke a demanding standard: rigorous, independent studies that demonstrate a clear and measurable impact on student learning outcomes—such as improved mathematics achievement, deeper conceptual understanding as evidenced in assessments, or stronger long-term retention.

Despite Liljedahl’s strong claims about the research underpinning BTC, these assertions have not gone unchallenged by the broader mathematics education community. Several external experts have expressed serious reservations about the strength of the evidence base. For example, Dr Anna Stokke, a prominent Canadian mathematics educator, has been openly critical of BTC’s research foundation, arguing that the evidence is weak and does not support the broad generalizations often made about its effectiveness.

As Stokke and other critics point out, the problem isn’t that BTC has no studies behind it—it’s that the studies being used to justify sweeping adoption don’t measure what matters most. Much of the BTC evidence focuses on engagement proxies: time on task, participation, or even the “non-linear” appearance of students’ work on vertical boards. But as Stokke noted, praising disorganization as a marker of thinking is “the opposite of what we want,” because mathematics is fundamentally about “precision, structure, and clarity.”

Dr. Zach Groshell makes a similar point from the practitioner’s side: BTC can function as “a cookbook of cool-sounding tricks that create a certain aesthetic—but offer no instructional substance.” And when the aesthetic becomes the selling point, the risk is obvious—schools may mistake visible activity for learning, while the central question remains unanswered: where is the independent evidence of improved achievement, retention, or transfer?

Greg Ashman, an education researcher and former mathematics teacher, has been unequivocal in his assessment of Building Thinking Classrooms. He characterizes BTC as “structurally unsound, epistemologically confused, and completely misaligned with cognitive science.” His critique focuses on BTC’s rejection of explicit instruction and its reliance on unguided problem solving, practices that research in cognitive load theory consistently shows are ineffective for novice learners. From Ashman’s perspective, the concern is not simply that BTC lacks sufficient empirical support, but that its core assumptions run counter to well-established principles of how students actually learn—calling into question its suitability as a foundation for mathematics instruction.

Taken together, these critiques point to a consistent and unresolved problem at the heart of Building Thinking Classrooms. The evidence most often cited in its defense documents changes in student behavior and classroom atmosphere, not demonstrable improvements in learning. External experts question the strength of the research base, cognitive scientists highlight misalignment with established principles of instruction, and even Liljedahl’s own studies stop short of measuring achievement or retention. Until BTC can show clear, independent evidence that it improves mathematical understanding—beyond engagement and participation—claims that it is “research-based” remain aspirational rather than empirical.

What “Building Thinking Classrooms” Is Actually Built On

The core of Building Thinking Classrooms rests on a small set of early studies conducted by Liljedahl examining how students behave when working at vertical non-permanent surfaces (VNPS), such as whiteboards, compared to working at desks or in notebooks. These studies form the empirical backbone of the BTC framework and are repeatedly cited throughout the book as evidence that the approach “works.”

What these studies primarily document, however, are changes in student behavior, not learning outcomes. Liljedahl’s observations focus on how quickly students begin working, how much they talk, how long they persist, and how visibly engaged they appear while standing at whiteboards. These behaviors are taken as indicators of “thinking,” but they are not accompanied by measures of achievement, conceptual understanding, retention, or transfer.

Crucially, the studies do not include pre- and post-tests, nor do they compare BTC classrooms to traditional classrooms in terms of learning gains over time. The research does not show that students taught using BTC perform better on assessments, master content more efficiently, or retain knowledge longer. The leap from increased participation to improved learning is assumed rather than demonstrated.

The measurement methods themselves introduce further limitations. Constructs such as “eagerness,” “discussion,” and “persistence” are scored through classroom observation, often by the researcher and participating teachers. This makes the findings vulnerable to observer bias, particularly when the behaviors being rewarded—movement, talk, and visible activity—are precisely those the intervention is designed to amplify.

In effect, the foundational research behind BTC establishes that changing the physical environment and task structure can make classrooms more animated and interactive. What it does not establish is that these changes improve mathematical learning. Yet it is this body of work—focused on engagement proxies rather than outcomes—that underwrites the book’s much broader instructional claims.

A Lesson from the Reading Wars

As a mathematics teacher, I care deeply about instructional approaches that are grounded in strong, peer-reviewed research—research that is controlled, replicable, and directly tied to student achievement, retention, and learning. That commitment isn’t ideological. It’s professional. And it’s shaped by what we’ve already seen happen in another subject area when those standards were ignored.

For decades, reading instruction in North America was dominated by Whole Language and later balanced literacy, most prominently through Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study. These approaches were built on compelling theories about immersion, meaning-making, and student engagement. They were widely adopted. They photographed well. And they were defended passionately. But they were not grounded in robust evidence of how children actually learn to read. Phonics and explicit instruction were dismissed as rigid or outdated—until the consequences became impossible to ignore.

When student reading outcomes stagnated and then declined, especially for the most vulnerable learners, the reckoning was swift and public. Media investigations, policy reversals, and large-scale curriculum revisions followed. The damage, however, had already been done—measured not in headlines, but in lost years of learning for millions of students.

The uncomfortable truth is that the early warning signs were there all along: reliance on engagement proxies, resistance to direct instruction, and claims of being “research-based” without clear evidence of improved outcomes. Those same warning signs are now visible in the rise of Building Thinking Classrooms.

This is not a claim that BTC has already caused the same harm, nor should it be avoided completely in the classroom. It is merely a warning that we are repeating the same pattern. As educators, we don’t get infinite do-overs. When we adopt instructional frameworks at scale, we are placing a bet on our students’ futures. That bet should be made on evidence, not aesthetics—on learning, not activity.

Math doesn’t need another reckoning. We already know how this story ends.

In the next article, I turn to a more practical question raised by this discussion: under what conditions does group work actually support learning in mathematics? Drawing on research, I will outline the instructional nonnegotiables that must be in place before collaboration can be assumed to produce understanding.

References

Ashman, G. (2024). Building thinking classrooms: Still nonsense, not supported by cognitive science. Filling the Pail.

Chi, M. T. H., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 49(4), 219–243.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.965823

Edutopia. (2023). How a podcast toppled the reading instruction canon.

https://www.edutopia.org/article/how-a-podcast-toppled-the-reading-instruction-canon/

Education Endowment Foundation. (2021). Explicit instruction.

https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk

Groshell, Z., & Stokke, A. (2024). Chalk & Talk Podcast, Episode 44: Mailbag — Building Thinking Classrooms.

Hanford, E. (2018–2023). Sold a story: How teaching kids to read went so wrong. APM Reports.

https://features.apmreports.org/sold-a-story/

Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 681–706.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.681

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86.

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

Liljedahl, P. (2016). Building thinking classrooms: Conditions for problem-solving. In P. Felmer, E. Pehkonen, & J. Kilpatrick (Eds.), Posing and solving mathematical problems (pp. 361–386). Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28023-3_21

Mayer, R. E. (2004). Should there be a three-strikes rule against pure discovery learning? American Psychologist, 59(1), 14–19.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.14

Rosenshine, B. (2012). Principles of instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator, 36(1), 12–19.

https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Rosenshine.pdf

Slavin, R. E. (1988). Cooperative learning and student achievement. Educational Leadership, 46(2), 31–33.

Stockard, J., Wood, T. W., Coughlin, C., & Rasplica Khoury, C. (2018). The effectiveness of direct instruction curricula: A meta-analysis of a half century of research. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 479–507.

https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317751919